Section One: The Problem

The problem is one of revelation. I understand one category of revelation to be "general revelation". This refers to God's communication of Himself to all persons at all times in all places by means of His creation, chronology, and human conscience. I understand a second category to be "special revelation". This refers to God's communication of his personal self to humankind through the incarnation of Christ and through His God-breathed Scripture. While reading Saint Augustine, I glimpsed a third category of revelation that is intermediate to special and general revelation. This is the attention-grabbing quote from Augustine written in about 397:

The Egyptians possessed idols and heavy burdens, which the children of Israel hated and from which they fled; however, they also possessed vessels of gold and silver and clothes which our forbears, in leaving Egypt, took for themselves in secret, intending to use them in a better manner… In the same way, pagan learning is not entirely made up of false teachings and superstitions … It contains also some excellent teachings, well suited to be used by truth, and excellent moral values. Indeed, some truths are even found among them which relate to the worship of the one God (de doctrina Christiana).1

Augustine wrote these words in the tradition of Justin Martyr who lived 150 years earlier:

We are taught that Christ is the first-born of God, and we have shown above that He is the reason (logos) of whom the whole human race partake, and those who live according to reason (logos) are Christians, even though they are accounted atheist. Such were Socrates and Heraclitus among the Greeks, and those like them(Apology). 2

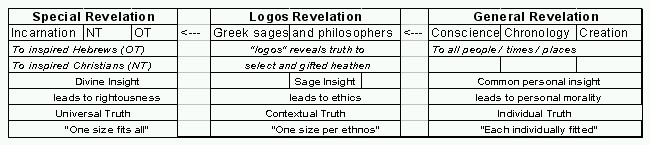

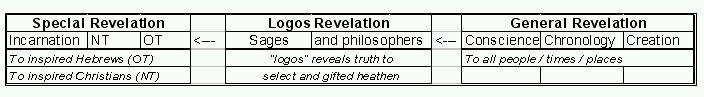

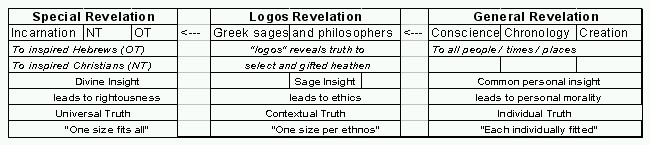

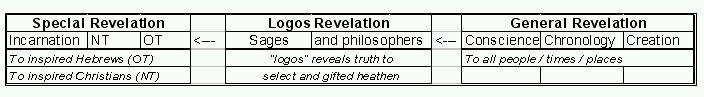

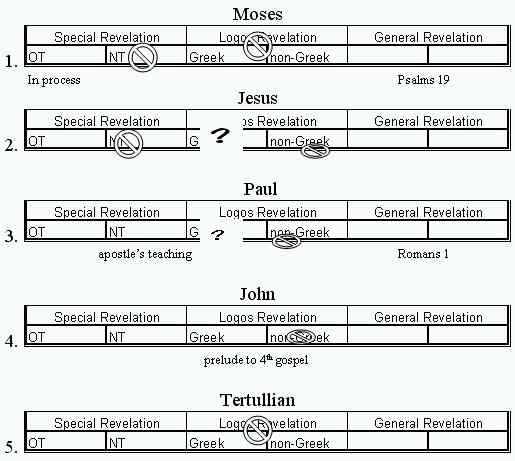

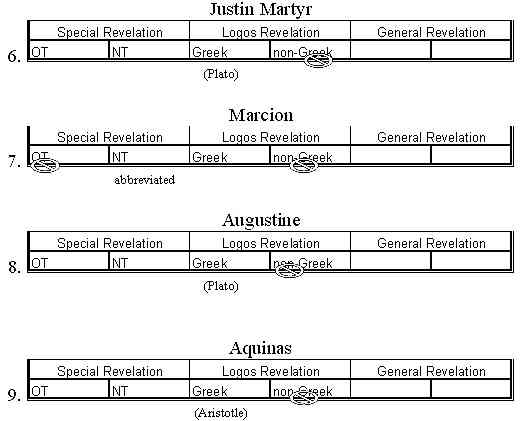

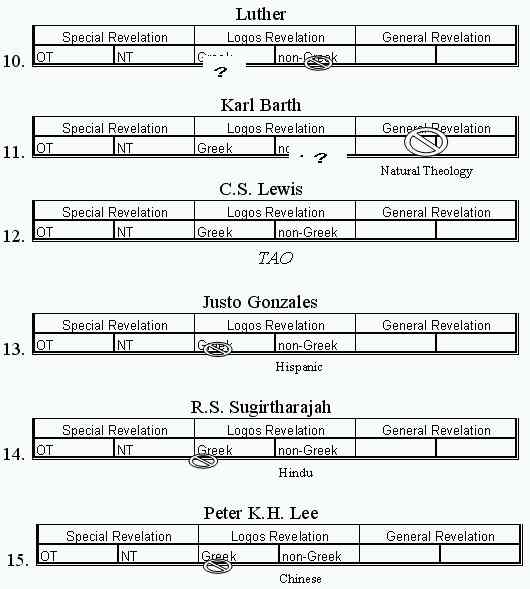

Both Augustine and Justin seem to allude to a third category of revelation which can be termed the "logos revelation". Since these two fathers of the church were immersed in Greek culture, they identify Greek sages as the source of this intermediate revelation. The chart below illustrates the place of logos revelation between special and general revelation.

In opposition to the Justin/Augustine position, Tertullian denied a logos revelation from the Greek philosophers. In his famed contrast between pagan philosophy and Christian theology he says,

What is there in common between Athens and Jerusalem? Between the Academy and the church Our system of beliefs comes from the Porch of Solomon, who himself taught that it was necessary to seek God in the simplicity of the heart. So much the worse for those who talk of a Stoic, Platonic or dialectic Christianity. We have no need for curiosity after Jesus Christ, or for inquiry after the gospel When we believe, we desire to believe nothing further. For we need believe nothing more than "there is nothing else which we are obliged to believe (On the Rule of Heretics). 3

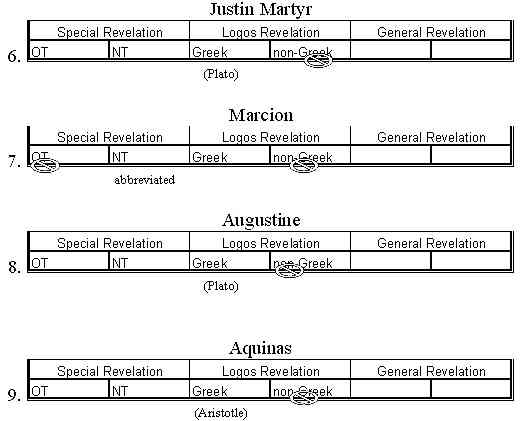

These are the two opposing "logos" camps of the early church. As the centuries progressed, the neo-Platonism of Augustine overwhelmed the "no-Platonism" of Tertullian. Greek philosophy became embedded in medieval Christian theology. Nine hundred years after Augustine, Thomas Aquinas shifted the focus of logos revelation. To use the imagery of Augustine, Aquinas took his vessels of gold from Aristotle rather than from Plato. The religious result was still a Greek logos, but one of neo-Aristotelian flavor rather than neo-Platonist flavor. By the time of the Reformation, Athens and Jerusalem became twin cities. One would find it difficult to tell where one city ended and the other began. It did appear as if the pagan Aristotle had been baptized and made a saint of the church. Although the Christian words may have been grounded in special revelation, the church spoke the language of logos revelation. Although the sights were still of a Christian heaven, the church viewed this sight through the colored lens of Greek philosophy. This is how Justo Gonzales describes the early Hellenization of Christianity:

While the earlier Christian apologists saw at least some of the crucial differences between Christian doctrine and Greek philosophy, as time passed some - eventually most-Christian theologians came to the conclusion that Scripture is best interpreted in the light of Greek philosophy-more specifically, Platonic philosophy.4

With the arrival of Protestantism, Athens was pushed into the background, but the Greek mindset was not entirely extinguished. Even today, most Protestant seminary professors are apt speak of God's attributes in Greek terms of "impassible" and "omnipresent". They do this in spite of the fact that these descriptions are derived more from reading Greek Philosophy than from reading the Greek Bible.

There is a new and emerging camp of theology that does not line up with Tertullian thinking nor with Augustine thinking. Like Tertullian, this camp does not place a high value on Greek Philosophy, but unlike Tertullian, they do support a version of "logos revelation". Like Augustine, this camp of theology recognizes "logos revelation", but unlike Augustine, these new theologians do not limit the "logos" light to ancient Greece. These new theologians, like Justo Gonzales, propose that ancient Greeks were not the only philosophers and sages to receive a special measure of logos insight from God. In his book Mañana, Gonzales suggests that the Hispanic world also has a "logos revelation" unique to its context. He terms this revelation that is especially delivered to people of Hispanic origin "The Spirit of Mañana" 5.

In this research, we have already introduced "logos revelation" as a possible third category of revelation. In the second part, we will examine the traditional catholic view of logos revelation. In the third part, we will focus on the view that is advocated by Justo Gonzales, which he calls "The Spirit of Mañana". We will also briefly look at a Hindu, Chinese, and African logos. In the fourth part, we will expand possible models of revelation to sixteen. We will also describe logos revelation in more depth and propose a model of logos revelation put forward by C.S. Lewis. |

Section Two: The "Greek Only Logos Revelation"

of catholic tradition

This traditional view can be thought of as the catholic view (note the lower case "c"). This is the way that Justo Gonzales describes the beginning of the long catholic tradition:

The clearest case is probably Justin Martyr, the second-century apologist whose work did so much to bring together Christian doctrine and Greek philosophy. Justin, like Plato before him, began with the notion that perfection requires immutability and thus agreed that the Supreme Being, God, must be immutable. How, then does that immutable God relate to this mutable world? Justin found his answer by drawing on the doctrine of the "logos" of ancient lineage among Greek philosophers. The logos then becomes the link between God and the world, between the mutable and the immutable.6

Gonzales goes on to say:

Joining this with the prologue to the Fourth Gospel, which speaks of the logos or "word" of god becoming incarnate in Jesus, Justin argued that all the great philosophers of antiquity knew, they knew because of the one who had become incarnate in Jesus This in turn allowed him to make the astonishing claim that, in a sense, Plato and Socrates were Christians-although he hastened to explain that they knew the logos only in part, where Christians who have seen Jesus have seen the entire logos.7

We should not be extreme in judging Justin in regard to his parochial view of the logos. After all, he was writing in an age when the Apostle John was recently deceased. This beloved apostle wrote of a "logos" that was obviously aimed at the Greek mind. Could not Justin claim to be simply expanding John's concept of logos? Second, Justin lived a dichotomous world of "Greeks and barbarians". His worldview was mono-cultural not multi-cultural, at least in the modern sense. Justin was not aware of large and ancient cultures (like Hindu or Chinese) that venerated philosophers of the same caliber as Plato and Aristotle. Third, Justin was carrying out a 2nd century apologetic in a thoroughly Greek world. He used Greek ideas to win over Greek minds. Are not 21st century Christians winning over post-modern minds by practicing a postmodern apologetic? This is how Justin Martyr explains his own theory of logos:

Whatever has been uttered aright by men in any place belongs to us Christians; for, next to God, we worship and love the reason (logos) which is from the unbegotten and ineffable God. … For all the authors were able to see the truth darkly, through the implanted seed of reason (logos) dwelling in them(Apology).8

As mentioned in Section One, two view were widespread in the early church. Tertullian advocated the "no-logos" view, keeping Athens away from Jerusalem. Justin advocated a Greek logos, building a church with foundations in both Athens and Jerusalem. It is the view of Justin that flourished and flowered in the teachings of Augustine. Logos Revelation of a neo-Platonist brand permeates the writings of Augustine, and Plato was present at the beginning of his religious life:

Having visited Bishop Ambrose, the fascination of that saint's kindness induced him to become a regular attendant at his preachings. However, before embracing the Faith, Augustine underwent a three years' struggle during which his mind passed through several distinct phases. At first he turned towards the philosophy of the Academics, with its pessimistic scepticism; then neo-Platonic philosophy inspired him with genuine enthusiasm. At Milan he had scarcely read certain works of Plato and, more especially, of Plotinus, before the hope of finding the truth dawned upon him.9

To Augustine and other Patristic Platonists, the Greek philosophy of Plato contained many "vessels of gold" that were worthy of use in Christian theology. However, Greek philosophy had to be re-worked and adjusted to match Christian doctrine. For example, to render the world of Ideas more acceptable to Christians, Augustine maintained that the world exists in the mind of God, and that this was what Plato really meant. According to Gonzales: "It is a well known fact that the omnipotent, impassible god resulted from the encounter between early Christians and the Greco-Roman world in which they were called to witness"10

The logos revelation of neo-Platonism continued through several centuries. After the crusades, contact increased with the Islamic world. By the circuitous route of Greek to Arab to Jew to Schoolman, Western Christianity re-discovered the writings of Aristotle.

When Platonism ceased to dominate the world of Christian speculation, and the works of the Stagirite began to be studied without fear and prejudice, the personality of Aristotle appeared to the Christian writers of the thirteenth century, as it had to the unprejudiced pagan writers of his own day, calm, majestic, untroubled by passion, and undimmed by any great moral defects, "the master of those who know".11

It is odd in the statement above that "no knowledge of Christ" is not deemed a "great moral defect" in is eyes of Catholic teaching. Just as Augustine had read the teachings of Plato in his years of Christian formation, so Thomas Aquinas read of Aristotle in his years of Christian formation:

The time spent in captivity was not lost. His mother relented somewhat, after the first burst of anger and grief; the Dominicans were allowed to provide him with new habits, and through the kind offices of his sister he procured some books -- the Holy Scriptures, Aristotle's Metaphysics, and the "Sentences" of Peter Lombard.12

The works of Thomas Aquinas climaxed with his Summa Theologica. This thoroughly Aristotelian text remains the basis of official Roman Catholic teaching to this day.

When the Western church split, Protestant reformers reverted to a logos position closer to Tertullian than to Justin. As Humanists preaching in the wake of Erasmus, they railed against the Scholasticism of Aquinas. By basing Christian faith and practice on "sola scriptura", these reformers increased the distance between Athens and Jerusalem. For example, when Luther was ordered before the general chapter of the order of Augustinians at Heidelberg in April 1518, he delivered his important "Heidelberg Theses". In these, Luther argued against the control of Aristotle in theology and outlined the leading features of his "theology of the cross". A second example involves the nature of he Lord's Supper. Almost from its beginning, the Catholic church has taught the real presence in the Eucharist. For one thousand years, the mechanism of this transubstantiation was a mystery. It was Thomas Aquinas who finally explained the mechanism, drawing heavily on the vocabulary of Aristotle. Once divorced from Rome, the Church of England continued the catholic doctrine of the real presence in the Eucharist. However, the Anglican church did not use the arguments of Aquinas / Aristotle to establish real presence. The mechanism of transubstantiation reverted to its pre-Aquinas mystery in both Anglican and Lutheran theology.

Most Protestants become catholic as they begin to speculate about the God outside of Scripture. Protestants often describe their deity according to Greek categories, although less rigorously than do Roman Catholics. For example, Millard Erickson says, "George Hegel, whose philosophy influenced much of nineteenth-century theology, believed in the Absolute, a great spirit or mind that encompasses all things within itself. .. The Biblical view is quite different. Here God is personal."13 When modern Christians - both Catholic and Protestant - speak of God as eternal, impassible, and impersonal, they follow a catholic tradition that goes back 1850 years to Justin. |

Section 3: Non-Greek Logos Revelation as exemplified by the "Spirit of Mañana"

As Europe was being torn asunder by the Protestant Reformation, Roman Catholicism was being planted in the New World. After these two grand events, Christianity would never be the same. In 1531, while Luther was completing his large catechism, a new logos was emerging in the New World. According to tradition, the Virgin Mary appeared to a man named Juan Diego, who was hurrying down Tepeyac hill near Mexico City. Our Lady of Guadalupe appeared as an Indian Mexican to Mexican believers. The Virgin's appearance, as a non-European, did much to further the Catholic cause in Mexico. This appearance also inaugurated what Justo Gonzales calls the Spirit of Mañana. This spirituality accepts the special revelation of the New Testament and the Old Testament, but rejects the logos revelation of Greek philosophy. This distinctive Hispanic voice is different from the Greek voice. According to this voice:

Christianity is not based on the distinction between spirit and matter. Indeed, such a distinction, if it appears in Scripture at all is a very secondary theme. Were we to say, as many take for granted, that such a distinction is the fundamental presupposition of Christian spirituality, and were we then to read Scripture in quest for guidance, we would be hard pressed. In the entire canon of Scripture there are not more than a few texts that could be cited as support for contrasting matter and spirit, and even these are subject to other interpretations. What has happened, as historians and Bible scholars know, is that during the early centuries of Christian history the contrast between matter and spirit, which was commonplace in Hellenistic religiosity, found its way into Christian theology and piety, to the point that later generations came to think that such a contrast was the mainstay of Christian spirituality. 14

According to Gonzales, the Spirit of Mañana is an eschatological expectation that is expressed in Hispanic churches. It means more than "tomorrow", but is a radical questioning of today. It is also a word of judgment on today. Mañana implies that the present is not as rosy as some would have us think. When English speakers wish to imply that Mexicans are lazy, they employ one of the few Spanish words they know, mañana. This word is usually meant as a rebuke to laziness. However, mañana is most often the discouraged response of those who have learned that no matter how hard they work, they will never get ahead. There is also hope in the mañana vision. The world will not always be as it is now.

Another key element of mañana spirituality is a truly liberative approach to the issues of society and political economy. This aspect is emphasized in Frontiers of Hispanic Theology in the United States, edited by Allan Figueroa Deck. In this collection of essays, Orlando O. Espin identifies six aspects of Hispanic spirituality.15 Through Jesus Christ, Hispanic believers find:

1. His true humanness

2. His true compassionate solidarity with the poor and suffering

3. His innocent death caused by human sin, and

4. His resurrection and divinity

Through the Guadalupe devotion, Hispanic believers find:

1. God's compassion and solidarity with the oppressed and vanquished

2. God's maternal affirmation and protection of the weakest

3. God's truth must be incarnated and acted out

Mañana spirituality, whether Evangelical or Catholic, always contains a measure of liberation theology. There is consistently a taking of sides against the rich in favor of the poor. This measure is downplayed by Justo Gonzales, but it is emphasized by most other Hispanic theologians.

The point made by Gonzales and other Hispanic theologians is that Greek philosophy is not the only source for "logos revelation". In fact, Greek philosophy may be a bad source of revelation and may distort the true meaning of Scripture. For cultures and ethnic groups outside the influence of Greek culture, insights provided by Plato and Aristotle may be of little significance. This is the point is brought home by Gonzales:

The new theology, being done by those who are aware of their traditional voicelessness, is acutely aware of the manner in which the dominate is confused with the universal. North Atlantic male theology is taken to be basic, normative, universal theology, to which then women, other minorities and people from younger churches add their footnotes. 16

If the Spirit of mañana describes a distinctive Hispanic logos, are there theologies in other cultures that claim a uniquely non-Greek logos? There are many, but allow me to enumerate three; Hindu, Chinese and African.

There is much written about a Hindu logos among Indian Christians. Like the spirit of mañana, this logos presents a theology large enough to encompass a suffering God:

Theology at 1200F in the shade seems, after all, different from theology at 700F. Theology accompanied by tough chapattis and smoky tea seems different from theology with roast chicken and a glass of wine. Now, what is really different, theos or theologian? The theologian at 700f in a good position presumes God to be happy and contented, well-fed and rested, without needs of any kind. The theologian at 1200F tries to imagine a God who is hungry and thirsty, who suffers and is sad, who sheds perspiration and knows despair.17

Unlike the logos presented by Hindu Christians that embraces a suffering God, the Chinese logos presents a God that is more stoic and Greek like. Peter K. H. Lee discusses this Chinese brand of Christianity in Frontiers in Asian Christian Theology: Emerging Trends. His use of the term "extratextual hermeneutics" is similar to my term of "logos revelation". He says that extratextual hermeneutics is an approach that tries to use indigenous literary and nonliterary resources for theological enquiry. It provides a helpful frame of reference for rethinking Chinese concepts in the Christian sense.18

In 25 pages, Lee examines the Chinese concept of "ch'i" which means breath or air. He compares ch'i with the Christian concept of spirit and Holy Spirit. He draws upon the great sages of China including Confucius and Tai Chen.

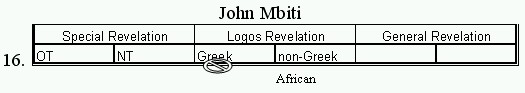

Although Christians in Africa represent a number of tribes and backgrounds they share some common aspects in an "African logos". John Mbiti observes that, "Because traditional religions permeate all departments of life, there is no formal distinction between the sacred and the secular, between the spiritual and material areas of life" .19 This logos harkens back to the mañana logos which diminishes the distinction between matter and spirit. Mbiti lists three distinctives of an African logos:20

1. Harmony - The world and life reflect a fundamental harmony that religion and ritual are meant to preserve or enhance.

2. God and the Powers - The material and spiritual worlds are ultimately part of a single reality, and the line between the one and the other is difficult to draw.

3. The Human Community - The worship of ancestors, the attitude to birth, death, sin, sickness, forgiveness and health converge on the central role of the community. The person cannot be destroyed because his or her existence is tied to the unity of all that exists.

The teaching point in enumerating these alternatives to a Greek-only logos is to demonstrate that the world is shifting. As Christians, we must answer the question: "Does Greek philosophy deserve a place of privilege in the universal church?" We must ask the parallel question, "Because the Greek logos has been the dominant logos for 2000 years, does this entitle it to next 2000 years?" A traditional catholic answer would be "Yes, the secrets of God's kingdom are best expressed in Greek concepts". The emerging answer is "No, every culture can find wisdom in its own context that accurately uncovers the secrets of God's kingdom".

To recast these questions in the imagery of Augustine, if the early church possessed the vessels of gold from the Greek sages, why cannot the later church possess vessels of gold from the sages of their own culture? Perhaps the words of Augustine also apply to Hindu pagans, Chinese pagans and African pagans: "In the same way, pagan learning is not entirely made up of false teachings and superstitions … It contains also some excellent teachings, well suited to be used by truth, and excellent moral values. Indeed, some truths are even found among them which relate to the worship of the one God." |

Section four: Figuring out what to do with Logos Revelation

Once again, here is the chart that places Logos Revelation between Special Revelation and General Revelation.

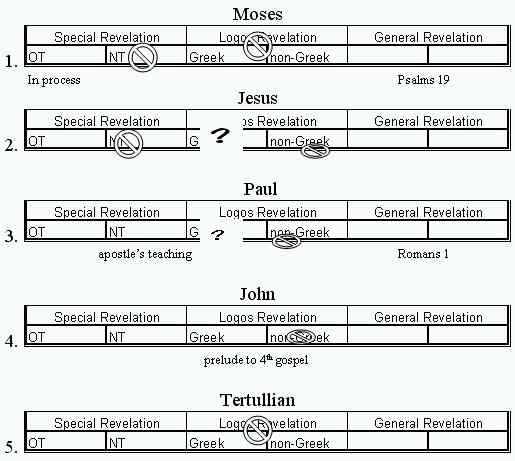

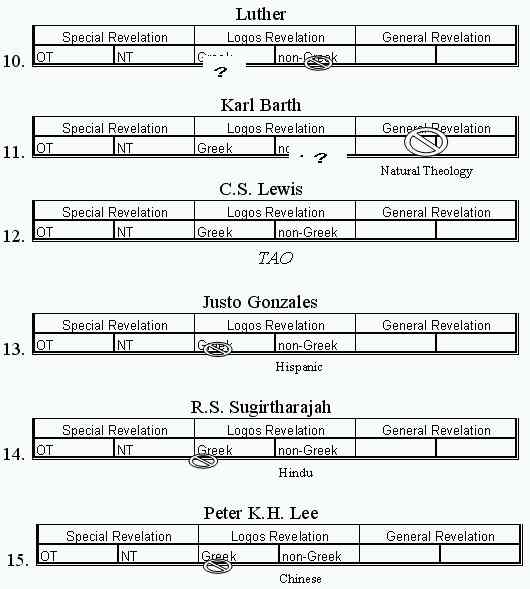

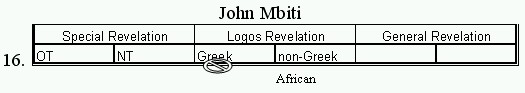

These are sixteen historical ways to view revelation, placed in a rough chronological order:

In looking at these sixteen ways of illustrating revelation, it is obvious that the most controversial and flexible portion is logos revelation. Most confessing Christians would not dispute the reality of special revelation or general revelation. They may differ in their interpretation of these two modes of revelation, but most would agree that such revelation exists. This is not true with logos revelation. What is the best way to define it? I propose the definition: "Logos revelation is that contextual voice of wisdom found in every culture that accurately uncovers the secrets of God's kingdom". Let me identify four characteristics of logos revelation.

1. It is a contextual truth, method, or way of thinking that applies to a people group or culture. It may hold wider utility or it may not. This is in contrast to the universal truth of Special Revelation that is applicable to all humans for faith and practice. This also contrasts with General Revelation which is dependent on individual enlightenment.

2. It leads to group ethics and a common standard of behaving. This is different from Special Revelation which leads to righteousness and it is different from General Revelation which may lead to personal morality.

3. It is typically expressed by the premier thinkers, authors, sages, or philosophers of a culture. This is distilled group wisdom as opposed to Holy Scripture which is inspired or to the natural world which reveals its secrets only to those with open hearts.

4. It is not to be confused with special revelation or usurp special revelation. We may agree with Augustine, that our logos revelation "contains also some excellent teachings, well suited to be used by truth, and excellent moral values". Yet we cannot follow logos revelation if it contradicts scripture.

I personally feel uncomfortable with the traditional catholic position. I do think that in the "fullness of time", Jesus appeared in a Greek-speaking culture. Scripture is written in Greek and Hebrew. This would seem to give these cultures a leg up on other logos revelations. Yet, the virtual canonization of Aristotle by Catholics makes me uncomfortable. In many places Greek teaching is against the plain sense of the Bible. After reading Gonzales, I feel a bit left out. I am one of those "North Atlantic males" who loves theology but who does not have a strong ethnic identity. I believe that the Gospel is more Greek than Gonzales portrays and I find it difficult to identify with his mañana spirituality. When all is said and done I often find myself in a position that most closely correlates with C.S. Lewis. I have read most of what he has written and there is no doubt that he fully embraces the Special Revelation of Scripture and the General Revelation of the world around us. In Mere Christianity, he entitles his first chapter "Right and Wrong as clues to the Universe". In this chapter, he discusses a logos revelation that speaks about right and wrong in a cultural context 21. He points out that all cultures throughout all time have had similar ethical codes. In another book called The Abolition of Man22, he terms this logos "the tao". He seems to be saying that God reveals himself in a limited way to cultural groups, speaking through the collective wisdom of their elders. I believe that this is similar to what I have been saying. And yet, Lewis does not denigrate the Greek logos. He recognizes that it is nearly impossible to separate he "Greekness" of apostolic writers and their Greek text from the universal truth that they are expounding.

I do recognize three categories of revelation. I do think that the middle category of "logos revelation" is slippery and difficult to define. I do give a special status to the logos of Greek culture, but that this status should not be overdone. I also agree that a unique logos can exist in various cultures and that these logos revelations can uncover the secrets of God's kingdom which in turn can enrich the fabric of the universal Church of Christ. |

Endnotes

1. McGrath, Alister E., editor. The Christian Theology Reader, 2nd edition. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001, page 9.

2. Ibid, page 4.

3. Ibid, page 5.

4. Gonzales, Justo. Mañana: Christian Theology from a Hispanic Perspective. Nashville: Abington Press, 1990, page 96.

5. Ibid, page 157.

6. Ibid, page 104.

7. Ibid, page 104.

8. Bettenson, Henry and Chris Maunder, editors. Documents of the Christian Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993, page 72.

9. Internet site: The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume II, 1907 by Robert Appleton

Company. Online Edition ,1999 by Kevin Knight. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01713a.htm (accessed 10/14/02).

10. Gonzales, Justo. Mañana: Christian Theology from a Hispanic Perspective. Nashville: Abington Press, 1990, page 96.

11. Internet site: The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume II, 1907 by Robert Appleton Company. Online Edition ,1999 by Kevin Knight.

Ibid, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01713a.htm (accessed 10/14/02).

12. Ibid, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14663b.htm (accessed 10/14/02).

13. Erickson, Millard J. Christian Theology, 2nd edition. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books,

1998, page 295.

14. Gonzales, Justo. Mañana: Christian Theology from a Hispanic Perspective.

Nashville: Abington Press, 1990, page 158.

15. Deck, Allan Figueroa, editor. Frontiers of Hispanic Theology in the United States.

Maryknoll, NY: orbis Books, 1992, page 76.

16. Gonzales, Justo. Mañana: Christian Theology from a Hispanic Perspective.

Nashville: Abington Press, 1990, page 52.

17. Sugirtharajah, R.S., editor. Frontiers in Asian Christian Theology. Maryknoll, NY:

Orbis Books, 1994, page 9.

18. Ibid, page 5.

19. Dyrness, William A. Learning about Theology from the Third World. Grand Rapids,

MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990, page 20.

21. Lewis, C.S. The Abolition of Man. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdsmans Publishing

Company, 1958.

22. Lewis, C.S. Mere Christianity. NY: The Macmillan Company, 1960.

|