Coincidence and Providence in the Book of Ruth

I. Reader Response

While reading through the textbook [Word Biblical Commentary: Ruth/Esther] I was struck by an idea that Bush discussed in regard to Ruth 2:3. In this portion of the narrative, Ruth leaves her mother-in-law, Naomi, and sets out by herself to glean. Ruth begins to glean on a plot of land belonging to her kinsman Boaz. The manner in which Ruth arrives at this plot of land is described by the Hebrew word  . Although all three verses of this narrative section in Ruth will be examined and diagramed, understanding the usage, meaning, context, and application of the word . Although all three verses of this narrative section in Ruth will be examined and diagramed, understanding the usage, meaning, context, and application of the word  is the goal of this exegesis paper. Of this word and passage, Bush says in the textbook:

"Although the noun occurs in 1 Sam 6:9; 20:26 with the meaning 'accident, chance,' the idiom is the goal of this exegesis paper. Of this word and passage, Bush says in the textbook:

"Although the noun occurs in 1 Sam 6:9; 20:26 with the meaning 'accident, chance,' the idiom  occurs elsewhere only in Eccl 2:14, 15, where it is usually translated 'fate befalls, overtakes.' In our context the idiom does not express the modern idea of 'chance' or 'luck', for that is foreign to OT thought. Rather, it signifies that Ruth, without any intention to do so, ended up gleaning in the field that belonged to Boaz. The translation 'as it happened she came upon' expresses nicely the absence of volition on Ruth's part (p. 104)." occurs elsewhere only in Eccl 2:14, 15, where it is usually translated 'fate befalls, overtakes.' In our context the idiom does not express the modern idea of 'chance' or 'luck', for that is foreign to OT thought. Rather, it signifies that Ruth, without any intention to do so, ended up gleaning in the field that belonged to Boaz. The translation 'as it happened she came upon' expresses nicely the absence of volition on Ruth's part (p. 104)."

"One must be careful not to read modern secular conceptions of 'fate' or 'luck' or 'chance' into this language. In the OT view God directly controlled all that happened. That this is the view of our author is abundantly clear from the way he attributes both the end of the famine in 1:6 and Ruth's conception in 4:13 directly to divine causality. Hence, 'chance' means here, as also in Ecclesiastes, that which happens without the intention or assistance of those involved and thereby expresses the conviction of the narrator that men cannot determine the course of events. This sentence indeed smacks of hyperbole - striking understatement intended to create the exact opposite impression (p. 105)"

Bush goes on to point out that the very secularism of the comment draws the readers' attention to it, reminding them subtly that even the accidental is directed by God.

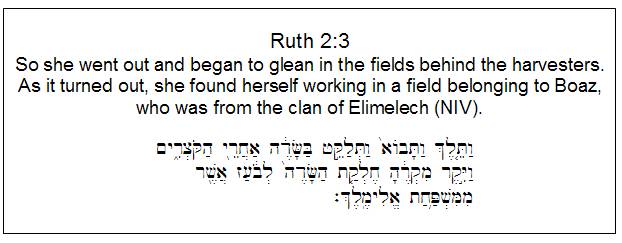

II. Translations of Ruth 2:3

The following seven translations of Ruth 2:3, translate  using five different terms: "luck", "hap", "happened", "turned out", and "chance". Contrary to what Bush states about luck being contrary to OT Hebrew thought, it is only the Jewish translation and not the six Christian translations that translates using five different terms: "luck", "hap", "happened", "turned out", and "chance". Contrary to what Bush states about luck being contrary to OT Hebrew thought, it is only the Jewish translation and not the six Christian translations that translates  as "luck". as "luck".

Jewish Publication Society

And off she went. She came and gleaned in a field, behind the reapers; and, as luck would have it, it was the piece of land belonging to Boaz, who was of Elimelech's family.

King James Version

And she went, and came, and gleaned in the field after the reapers: and her hap was to light on a part of the field belonging unto Boaz, who was of the kindred of Elimelech.

New American Standard Bible

So she departed and went and gleaned in the field after the reapers; and she happened to come to the portion of the field belonging to Boaz, who was of the family of Elimelech.

New International Version

So she went out and began to glean in the fields behind the harvesters. As it turned out, she found herself working in a field belonging to Boaz, who was from the clan of Elimelech.

New Jerusalem Bible

So she set out and went to glean in the fields behind the reapers. Chance led her to a plot of land belonging to Boaz of Elimelech's clan.

Revised Standard Version

So she set forth and went and gleaned in the field after the reapers; and she happened to come to the part of the field belonging to Boaz, who was of the family of Elimelech.

Young's Literal Translation

And she goeth and cometh and gathereth in a field after the reapers, and her chance happeneth -- the portion of the field is Boaz's who is of the family of Elimelech.

Verbal links to Ruth 2: 1-3

Before further examining the Hebrew word  , this paper will first consider all three verses that make up this section of Ruth.

1 Now Naomi had a relative on her husband's side, from the clan of Elimelech, a man of standing, whose name was Boaz. 2 And Ruth the Moabitess said to Naomi, "Let me go to the fields and pick up the leftover grain behind anyone in whose eyes I find favor." Naomi said to her, "Go ahead, my daughter." 3 So she went out and began to glean in the fields behind the harvesters. As it turned out, she found herself working in a field belonging to Boaz, who was from the clan of Elimelech (Ruth 2:1-3 NIV). , this paper will first consider all three verses that make up this section of Ruth.

1 Now Naomi had a relative on her husband's side, from the clan of Elimelech, a man of standing, whose name was Boaz. 2 And Ruth the Moabitess said to Naomi, "Let me go to the fields and pick up the leftover grain behind anyone in whose eyes I find favor." Naomi said to her, "Go ahead, my daughter." 3 So she went out and began to glean in the fields behind the harvesters. As it turned out, she found herself working in a field belonging to Boaz, who was from the clan of Elimelech (Ruth 2:1-3 NIV).

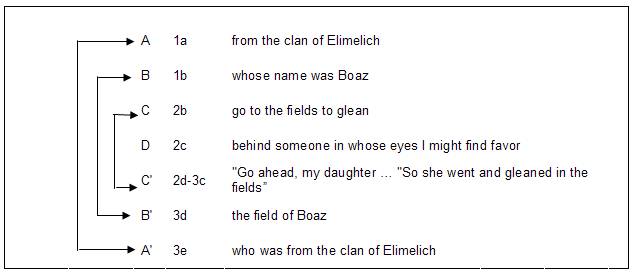

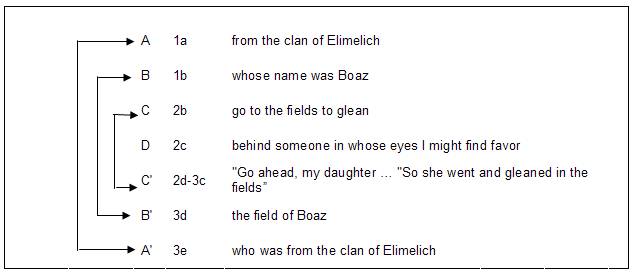

This three-verse passage is a bridge between the events that happened in chapter one -- the family in Moab and on the road Bethlehem -- and a longer 13-verse passage in chapter 2 that describes the initial encounter between Ruth and Boaz. In these three verses there are two references that link back to 1:2 where Naomi's husband is named as "Elimelech". We see a new name "Boaz" who is twice referred to as being "from the clan of Elimelech". Throughout the Ruth narrative, six references to Elimelech keep him involved in the story, although in a small way. Two of these references to Elimelech occur in this passage, one at the beginning and a second at the end of this passage. These two references therefore function as an inclusion around verses 1-3. Another link is the term "Ruth the Moabitess", a phrase that is used six times in Ruth. This term intends to convey Ruth's foreignness in Bethlehem, but it also links together the several passages and draws our thoughts back to chapter one and the origins of Ruth in Moab. The term "fields" reminds us of the "fields of Moab" that were left behind by Naomi and Ruth. There is also a link in the manner in which Ruth returns to the fields in Bethlehem. As chapter one begins, Naomi and Elimelech leave Bethlehem to seek for bread in a foreign field. Now Ruth (the Moabitess) has left Moab to seek bread in Bethlehem. She is about to begin this bread-seeking as a gleaner of the fields. This three-verse passage also forms a chiasm suggesting both its unity and its boundaries as a pericope.

Exegetical Outline of Ruth 2: 1-3

I. Ruth asks Naomi's permission to go and glean in the fields of Bethlehem.

A. Ruth speaks to Naomi to get permission to go and glean.

1. Ruth speaks to Naomi.

2. Ruth asks Naomi to go and glean and to find someone kind enough to let her gather food.

a. Ruth asks to glean among the sheaves.

b. Ruth asks to seek to glean where she would be permitted.

B. Naomi gives Ruth permission to go and glean.

1. Naomi speaks to Ruth.

2. Naomi commands Ruth to go and glean.

II. Ruth goes and gleans in Boaz's field.

A. Ruth goes out in search of a place to glean.

1. Ruth leaves Naomi to go and glean.

2. Ruth comes to the field of Boaz.

3. Ruth gleans in the field, following the reapers.

B. Ruth happened upon the field of Boaz.

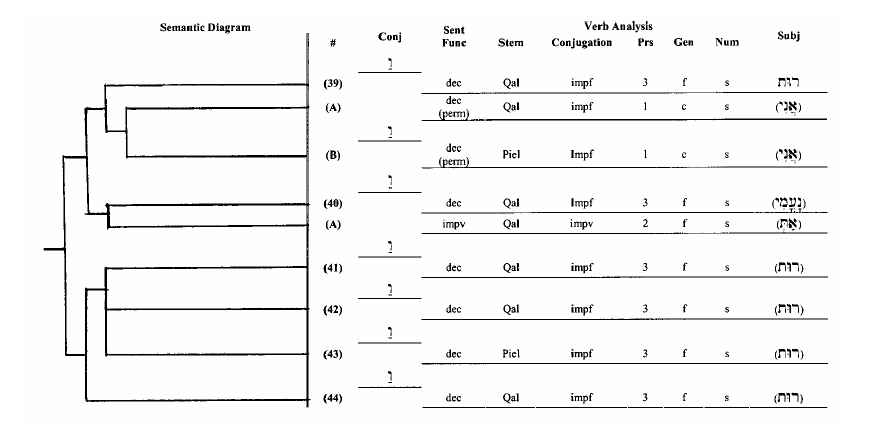

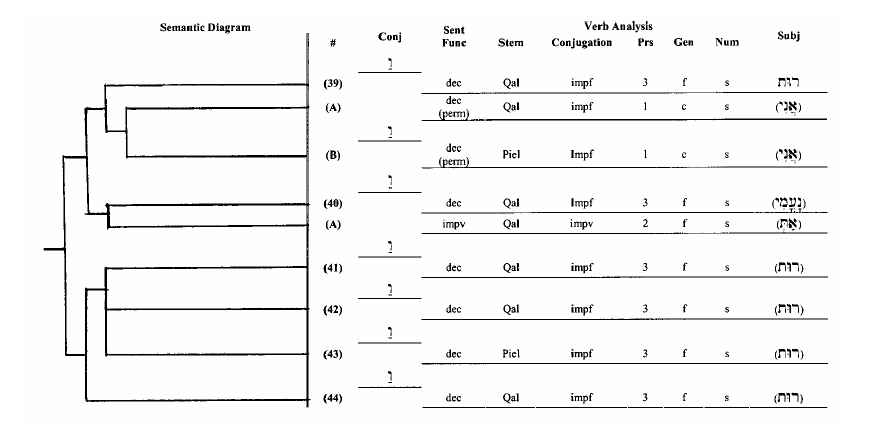

Semantic Diagram of Ruth 2: 1-3

Below is a semantic diagram of this three-verse passage based upon the exegetical outline.

Note that the diagram consists of nine main clause statements, all but one being declarative. The nine statements are connected together by seven waw consecutives. The diagram also shows seven of the nine statements occurring in the Qal stem and two in the Piel stem. There are two major divisions in this passage: the first centers in the dwelling place of Ruth and Naomi and the second in the gleaning field of Boaz.

Description of Semantic Diagram of Ruth 2: 1-3

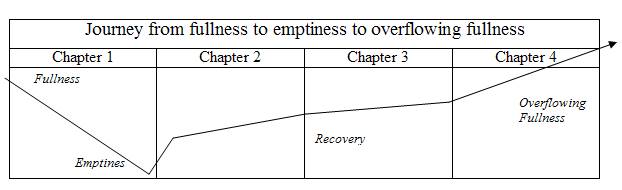

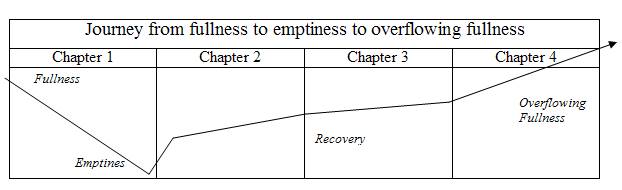

As chapter one concludes, the story hits its low point. Naomi, whose name means "sweet", has just declared that her name is now Mara, which means "bitterness". She says that she had left Bethlehem full and has returned empty. This passage marks the beginning of the climb up from this narrative low point as the diagram below illustrates.

The first glimpse of hope appears as we see the name of "Boaz" in close proximity to the term "one in whose eyes I may find favor". We ask ourselves, "could Boaz be this person?" In this passage, the position of protagonist changes. In chapter one, the central figure was Naomi. Beginning with this passage and continuing through chapters two and three, the action moves away from Naomi and shifts to Ruth and Boaz. It is interesting to note that as the narrative concludes, the focus again returns to Naomi in the order of a grand chiasm. Verse one introduces Boaz into the narrative as both a mighty man and a kinsman. The name of Elimelech is also invoked. Verse two includes a short verbal exchange. Ruth asks Naomi for permission to glean in the fields and Naomi gives her consent. There is some controversy about the assertiveness of Ruth's request. The Hebrew leaves it ambiguous as to whether her words were a polite entreaty or a flat-out assertion ("May I go" vs. "I will go"). The proper interpretation is probably somewhere between these poles. Ruth is half-way polite and half-way assertive. In no way, however, is she disrespectful to Naomi. Verse three describes Ruth going out and "happening" to find the field of Boaz, once again emphasizing that this man is a kinsman of Elimelich, who was the wife of Naomi who is the mother-in-law of Ruth. The Hebrew word for this "happening" is  which will be the focus of further discussion. which will be the focus of further discussion.

Commentary and Journal Article Work about Ruth 2: 3 and the idea of

For this research paper, I consulted four commentaries and one journal article. The New American Commentary by Daniel I. Block offered these thoughts about  as the word appears in Ruth. as the word appears in Ruth.

"The meaning is illuminated by 1 Sam 6:9 where it expresses the Philistine notion of chance: if the cows do not carry the Ark of the Covenant to Beth-Shemesh, they will know that their calamities are not attributable to the hand of God; they have happened by chance. In this context the narrator draws attention to Ruth's chance arrival at the field of Boaz even more pointedly with the redundant phrase 'her chance chanced upon' which in modern idiom would by rendered 'by a stroke of luck' (p 653).

The author, Daniel I. Block, further points out that the statement is ironical. He says that the orthodox Israelite did not believe in chance at all. The proverb declares "The lot is cast into the lap, but its every decision is from the LORD (Proverbs 16:33)." Block suggests that this phrase is better interpreted as a deliberate rhetorical device on the part of the narrator. "By excessively attributing Ruth's good fortune to chance, he forces the reader to sit up and take notice, to ask questions concerning the significance of everything that is transpiring (p 653)". It screams out "see the hand of God here".

The IVP Woman's Bible Commentary only mentions this section of Ruth briefly. The editors say: "Having introduced the reader to Boaz, Ruth 2:3 reveals that Ruth is providentially working in Boaz's field". The word "providence" which means "divine guidance or care" seems to be a fitting word to describe how Ruth came upon this field. The word "miracle" is too strong. The word "coincidence" is to weak. The words "destiny" and "fate" appear neural in regard to divine guidance, but the words "chance" and "luck" appear to mean events outside the care of God.

The Commentary on the Holy Bible by Matthew Henry seems to agree that "providence" may be the best word that describes Ruth coming upon the field of Boaz. Although the observations are dated, they still are helpful in understanding the text:

"She trusts Providence to raise her up some friend or other who will be kind to her. And God did well for Ruth; for when she went out, without guide or companion, she went to the field of Boaz. To her it seemed casual; she knew not whose field it was, nor had she any reason for going to that more than any other; therefore it is said to her hap; but Providence directed her steps to this field (p 121)."

Matthew Henry then goes on to comment that affairs which seemed by chance to us are directed by Providence with design.

In The Anchor Bible: Ruth, Edward F. Campbell, Jr. says of  : :

"Both verb and noun are built from the root qrh, 'to befall, happen.' The LXX translators dutifully reflect the Semitic structure by using a Greek known derivation of the verb, even though they had to stretch the noun's meaning a bit, since it usually meant 'calamity'. The notion of chance or accident is not usually a nuance of the Hebrew root's meaning (p 92)."

Campbell then goes on to say much of the same thing that Block says. These words that mean "luck" or even "calamity" are ironic to the extreme. The ancient reader would know at once that the narrator was drawing Yahweh into the story as the one making the luck happen.

I also reviewed a journal article entitled: "The Hebrew Terminology of Lot Casting and Its Ancient Near Eastern Context," by Anne Marie Kitz. In this article, Kitz discusses the ancient Hebrew method of lot casting and compares it to lot casting in other ancient Near East cultures. The concept is clear. Ancient Hebrews cast lots to determine God's will. The winning lot was determined not by man, nor by chance/destiny/fortune/luck, but by divine will. Yahweh himself did the choosing. This Hebrew concept of providence in lot casting continued into New Testament times. In Acts 1:23-26, we read:

"So they proposed two men: Joseph called Barsabbas (also known as Justus) and Matthias. Then they prayed, 'Lord, you know everyone's heart. Show us which of these two you have chosen to take over this apostolic ministry, which Judas left to go where he belongs.' Then they cast lots, and the lot fell to Matthias; so he was added to the eleven apostles (NIV)."

This method of lot casting indicates that even the most artificially contrived "game of chance", is able discern God's will. Although this journal article did not mention Ruth, the author emphasized the fact that "luck" was not a part of the Hebrew worldview. Events happened either because of human will or intervention, or because of divine will or intervention. In the case of Ruth coming upon the field of Boaz, there was no human will or intention involved. Therefore, the result must clearly come from the hand of God.

Synthesis

An examination of Ruth 2:1-3 shows this passage to be a critical transition from the depths of emptiness to the beginning of fullness. These three verses mark the beginning of recovery. Besides this new beginning, the narrator mentions two other events worthy of note. One event is the introduction of Boaz into the narrative drama. This man of worth will provide the means of restoration for Ruth and Naomi. A second event is the switching of positions between Naomi and Ruth. Ruth now becomes narrator's primary focus and Naomi plays the supporting role. Additionally, this passage is noteworthy because it suggests the intervening hand of Yahweh. We see this hand demonstrated in Ruth by three major events. The first event is the famine that forced Naomi and her family into Moab. The second event occurs here in 2:3 when Ruth "happens" upon the field of Boaz. The third divine intervention causes Ruth to bear a son to remove the shame of Naomi. It is here in Ruth 2:3 where the hand of Yahweh appears most subtle. The Hebrew word  is recognized to be ironic by nearly all interpreters of Ruth. Most scholars recognize the wide semantic range of this word, and they may translate it differently. However, all agree that the narrator of Ruth intends by these words to show the providence of God in leading Ruth unto the field of Boaz. In other words, however one may phrase it, it was Yahweh who accomplished it. is recognized to be ironic by nearly all interpreters of Ruth. Most scholars recognize the wide semantic range of this word, and they may translate it differently. However, all agree that the narrator of Ruth intends by these words to show the providence of God in leading Ruth unto the field of Boaz. In other words, however one may phrase it, it was Yahweh who accomplished it.

Application in a current setting

As human beings we can interpret unexpected favors in several ways. One way is to attribute this unexpected favor to "random luck" or "good fortune". This attribution denies any plan or design behind the favor. A second way might be to use the word "coincidence". This is neutral term which denies the existence of both luck and providence. A third way might be to describe the special favor as "destiny" or "fate". These words hint at a plan or design to life, but in an indirect way. A fourth way is to attribute the unexpected favor to "providence" or "divine intervention". When the book of Ruth was written, the narrator understood this range of possible interpretations to a favorable happening. In an ironic way, the narrator uses the word  which does mean "luck", to describe Ruth happening upon the field of Boaz. However, the context in which h'r<êq.mi is used leaves little doubt that the narrator intended his audience to see the hand of Yahweh clearly behind the good fortune of Ruth. which does mean "luck", to describe Ruth happening upon the field of Boaz. However, the context in which h'r<êq.mi is used leaves little doubt that the narrator intended his audience to see the hand of Yahweh clearly behind the good fortune of Ruth.

How do people react to favorable happenings in 2003? Do we attribute our good fortune to God, or to coincidence, or to luck? I believe that little has changed in 3000 years, since the days when judges ruled in Israel. As 21st century narrators of our own lives we continue to interpret our own encounters with good fortune in a number of ways. Each of us can probably point to at least one event in our personal life when something extraordinary happened, equivalent to Ruth stumbling upon the field of Boaz. The manner in which we interpret the event tells more about ourselves, than about the event.

I have attached a story that appeared in Parade Magazine on April 13, 2003. This article, which was widely distributed across America, is entitled "I Always Knew I'd Find Him". In brief, this story relates how a sister found her brother against impossible odds. The brother was adopted at birth and the adoption records were closed. The sister, who was six years younger, did not learn that she had an older brother until she was 17 years old. Then she became obsessed with finding him. After years of searching the trail drew cold. Both the sister and the brother eventually moved to San Francisco, only two miles apart. When the sister was 28 and the brother was 34, they went to dinner together at the request of a mutual friend. After excited conversation they realized that they were sister and brother. This article begins with this line: "When exactly does the border between coincidence and fate begin to blur?" Seven other phrases used in this article are (1) "A chance encounter" (2) "grew up linked, by genetics or coincidence or an unseen hand." (3) "remarkable symmetry of their lives" (4) "amazed by the forces they believe guided them together." (5) "makes me believe in destiny." (6) "Whether you call it destiny or dumb luck." (7) "there's a force behind everything." These are seven ways that 21st century Americans speak of a Ruth-like happening. The book of Ruth is relevant today because the same "force behind everything" that once lead Ruth unto the field of Boaz is also at work today, leading a sister into the path of her long-lost brother. Providence is no coincidence. Providence ( ) is God's care for us. ) is God's care for us.

Bibliography of fifty citationsomitted from web version

|