John Glenn orbits the Earth

All the astronauts were big media stars in the early 60s. Here's a fifth grade joke: "Question -- Why did America send Alan Shepard up into space? Answer -- Because after all the sheep that Russians and Americans have sent up, they needed a shepard." John Glenn was the most famous of all the astronauts, even more famous than the first to step on the moon, Neil Armstrong. I don't remember the listening to the news of his flight, but I do remember how big the space race was in those days. All the boys in class professed to become astronauts when they grew up. I wanted to be a teacher. Listen to news of John Glenn's flight. |

|

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union

launched Sputnik I, a 184-pound comet

shaped satellite. Every 98 minutes, Sputnik

passed overhead in orbit, its radio

transmitter beeping a distant, high pitched

signal. Its flight marked the start of the

space race between the US and the USSR.

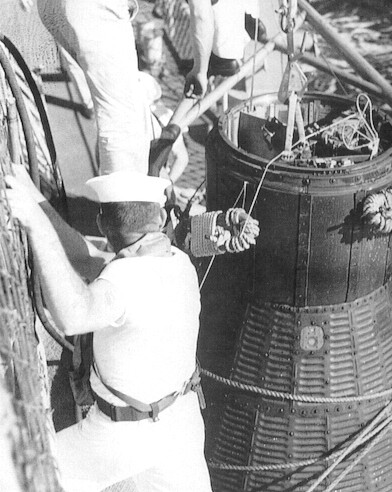

The New York Times headline read: Any dim hope that Sputnik was a singular event was shattered on November 3 when the Soviets launched Sputnik II. On board was a much heavier payload -- including a dog named Laika. There could be only one reason to put a dog into space: it was a first step toward putting a man in orbit. To close the "space gap," the President ordered the creation of Project Mercury. The goal was to explore the potential of putting man in space. Among the top priorities -- the selection of the first astronauts. Applicants were drawn from the ranks of jet qualified test pilots. After intensive interviews, the field was narrowed from 110 qualified applicants to just seven. These would be the men to take the United States into space. The oldest of the Mercury Seven and the only Marine pilot was Lieutenant Colonel John H. Glenn, Jr. Lieutenant Commanders Alan B. Shepard, Jr., and Walter M. Schirra, Jr., and Lieutenant M. Scott Carpenter were Navy fliers, while Captains L. Gordon Cooper, Jr., Virgil I. Grissom, and Donald K. Slayton were from the Air Force. Each had in excess of 1,500 hours' total flying time when they entered the program. In April of 1959, John Glenn entered into the space program as a Project Mercury Astronaut with NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center. For those who knew him well, it was no surprise that Glenn had been selected for this elite test program. On February 20, 1962, Glenn boarded the Mercury-Atlas 6 Friendship 7 spacecraft for the first manned orbital mission of the United States. Clambering into the spacecraft, he knew the risks but also knew that it would be his moment. He was at the door of history. The countdown was not smooth, as was common on all Mercury missions. Finally, after a number of temporary clock holds, the final countdown began. "...5, 4, 3, 2, 1...." With a gentle but constant push, the Atlas rocket launched Friendship 7 skyward and into space. The capsule accelerated, pitching slowly downrange over the open Atlantic. At the point where the two prior missions turned earthward for splashdown, Glenn's rockets were still firing. He reached a maximum altitude (or apogee) of 162 miles and an orbital velocity of approximately 17,500 miles per hour. Glenn's flight involved a series of tests to measure man's reaction to extended zero-g flight and to push the limits of the spacecraft. The foremost challenge was whether a man could control the spacecraft's flight path with rocket thrusters. Many engineers felt that the flight control system, an area in which Glenn specialized, would be too touchy for human control. Most felt the autopilot would have to fly the spacecraft. The plan was simple: he would switch off a single axis of control from the autopilot, and fly that portion manually. For instance, he would leave it engaged for pitch and roll while he tested yawing the capsule to the left and right. If it began to oscillate uncontrollably, he would quickly return the capsule to autopilot flight while the experiences were studied. If all went well, in the final orbit he would attempt all axis' of control for a short while. However, the automatic flight system malfunctioned. A yaw attitude control jet clogged, forcing Glenn to switch off the automatic control system and take over direct control by hand with the manual-electrical fly-by-wire system. Without difficulty, Glenn flew all axis' of the flight control system at once. Throughout the flight, he continued experimenting with the Mercury capsule's flight characteristics. With each maneuver, Glenn extended the control inputs to see how the capsule performed in the vacuum of space and without the aerodynamics of flight within the atmosphere.  After the reentry, the capsule's 'chute blossomed beautifully above, slowing its decent into the water. Friendship 7 had landed. Floating on the waves in the open Atlantic, Glenn rested while waiting for the helicopters to arrive. A miscalculation of the capsule weight from not subtracting burned fuel meant the splashdown was fully 41 miles west and 19 miles south of the originally planned point. The capsule was almost 800 miles to the southeast of Cape Kennedy, not far from Grand Turk Island. After three orbits, his time aloft from launch to impact was 4 hours, 55 minutes, and 23 seconds .Now, Glenn was back on earth. Once on board the Navy Destroyer USS Noa, he examined his capsule. Despite it's problems, the mission was the most successful in the program. It had been a ride to last a lifetime. |