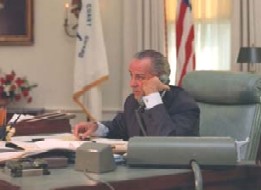

President Johnson declines to run for President

Listen to a news conference where LBJ announces that he does not choose to run. |

Johnson's domestic proposals in 1967 and 1968 reflected his awareness of new limits on his power. Although he continued to insist that the country could afford both the war in Asia and the Great Society programs at home, his critics charged that the United States could not pay for both "guns" and "butter." Moreover, they said, the demands of the war drained funds from vitally needed domestic programs. Inflation, which had been moderate in the Kennedy and Eisenhower administrations, rose sharply. Rioting in the black neighborhoods of many large cities, sporadic for several years, reached a peak in the summer of 1967. Johnson admitted that the riots revealed that not enough was being done to solve the problems in the cities, and he insisted that suppression, while necessary (he did send federal troops into Detroit), was not enough. But he did not call for bold new programs or substantial enlargement of established ones. Instead, he called for enactment of proposals made earlier and tried to press business leaders to assist the urban poor. The war now occupied the top spot on Johnson's agenda. He continued to reject suggestions that bombing of the north should be stopped, and he drew instead on the advice of advocates of emphasis on military pressure. By 1968, U.S. troop level was close to 500,000. The Vietcong and North Vietnamese, however, suddenly mounted a major offensive early in 1968. It contradicted the administration's optimism and enlarged the ranks of Johnson's critics. Two Democratic critics now moved forward. Senator Eugene McCarthy demonstrated surprising strength in the New Hampshire presidential primary in a contest with Johnson. Then, Senator Robert Kennedy announced that he would also seek the presidency. In this situation, Johnson announced two major decisions on March 31. The first was a pause in the bombing of almost all of North Vietnam; the second, his determination not to seek another term. Subsequently, public approval of his leadership jumped again; Congress endorsed his proposals for fair housing and a tax increase; and negotiations with North Vietnam began in Paris. The period of success was brief. Congress offered new resistance to his proposals. The Paris negotiators made no progress. Although the Democrats nominated Hubert Humphrey, Johnson's choice as his successor, Johnson's absence from the convention suggested his weakening grip on the party. Many former supporters of McCarthy and Kennedy refused to support Humphrey, while George Wallace gained much support as a third-party candidate. In October, the Senate failed to approve Johnson's nomination of Abe Fortas to be chief justice of the United States. In November, Humphrey lost to the Republican candidate, Richard M. Nixon, a result regarded as an expression of public disapproval of the Johnson administration.

Although Johnson halted the bombing of North Vietnam entirely on November 1, the Paris peace talks made no significant progress. Furthermore, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 helped frustrate the president's hopes for a summit meeting to deal with arms reduction and other problems. Johnson left office on Jan. 20, 1969, with his hopes for world peace unrealized. |

I always liked LBJ. He seemed down-to-earth. He was my president when I was in High School, just learning about what presidents are all about. It came a shock to learn of his withdrawal from the campaign. I remember him taking the oath of office and also signing the Civil Rights Act. His policy in Viet Nam was a big problem. If only he had stopped fighting World War II and had realized Viet Nam was a whole different place. I believe if LBJ would have just pulled out of Viet Name in the Spring, he could have won the election in the Fall.

I always liked LBJ. He seemed down-to-earth. He was my president when I was in High School, just learning about what presidents are all about. It came a shock to learn of his withdrawal from the campaign. I remember him taking the oath of office and also signing the Civil Rights Act. His policy in Viet Nam was a big problem. If only he had stopped fighting World War II and had realized Viet Nam was a whole different place. I believe if LBJ would have just pulled out of Viet Name in the Spring, he could have won the election in the Fall.