This morning we are to explore the strange city of Seoul.

A Korean who speaks English acts as our guide, and we are escorted also

by two of the native soldiers who are furnished to our legation by the

king. There is no danger, but appearances are everything in Korea,

and great people, among whom we are now classed, since we are the guests

of the minister from the United States, never go out without soldiers and

servants about them.

We have to watch where we step. The streets in most

parts of the city are narrow and winding, and the sewage flows through

them in open drains which take up much of the roadway. There were

until lately no waterworks in Seoul except the Korean water carrier, who

almost fills the street as he goes from one part of the town to the other,

carrying his two buckets, hung one on each end of a pole across his back.

The clouds still do much of the work of sprinkling the streets, and the

servants still take dippers and ladle the dirty water out of the sewers

to settle the dust.

The smell is disgusting at times, and mixed with it just

now is smoke, for all Seoul is cooking its breakfast. Each of the

huts has a chimney which juts out into the street at right angles with

the wall, about two feet from the ground. The people use straw for

fuel, and this produces the great smoke which the chimneys are pouring

out into the streets.

Ours eyes smart as we walk on through the city.

We try to keep out of the way of the porters, the water carriers, and the

people who are going to the markets, which are situated at the foot of

the chief business street, and about the gate through which we entered

the city. We follow the crowd, and soon find ourselves in the busiest

place in Korea.

There are thousands of men in all sorts of costumes, selling

and buying. There are porters by scores who have brought loads of

fresh fish from the seashore on their backs over the mountains, and there

are butchers by dozens who are selling beef, venison and other kinds of

game. There are booths devoted to the selling of rice. White-gowned

men squat on the ground with bushels of red peppers before them.

There are boys peddling Korean matches, which are shavings with their ends

dipped in sulphur, and which have to be touched with a burning coal before

they will light. There are hundreds of men buying grain, and carrying

on all sorts of wholesale and retain business.

|

|

The sales are not large, and things are bought

by handfuls rather then bushels. Some articles seem very curious.

Eggs are sold by the stick, ten being laid end to end and wrapped around

with long straw so tightly that they stand out straight and stiff.

A stick of ten eggs brings about three cents. Here is a man selling

pipe stems. The most of them are as long as himself, for the Korean

gentleman’s pipe is so long that he has to have a servant to light it,

as he cannot reach out to its bowl when the stem is in his mouth.

|

|

See that man in a black hat and white gown, with

a pile of clubs before him! They are not unlike baseball bats, and

we wonder if our American game has not been brought out to Korea.

We ask our guide, and he tells us those are ironing clubs, and shows us

how the women use them for ironing. The clothes are first washed

in cold water and dried on the grass. They are then taken into the

house and wrapped around a stick, which is laid on the floor. Now

one or two women squat down before the stick, and pound upon the cloth

with these wooden clubs until it becomes as smooth and glossy as the best

work of an American laundry.

Our guide points to his own gown of snow white, and tells

us that it was ironed in this way, and as we go on through the city we

hear the musical rat-tat-tat which comes from the ironing. This noise

is to be heard throughout Seoul at every hour of the day, and during nearly

every hour of the night. The garments are such that they must be

ripped apart whenever they are washed. It takes a long time to iron

them, and when they are finished they must be again sewed together, so

that you see Korean girls have quite as much to do as our girls at home.

|

"and pound upon the cloth"

|

|

|

A Korean Lady

A Korean Lady

|

We learn that only the higher-class women receive

any education, and that very few know how to read. After girls are

seven years old they must stay in the women’s quarters in the backs of

the houses, and must no longer play with the boys. The noble women

will not go out on the street except in closed chairs, and poorer women

whom we meet during our tour have green cloaks thrown over their heads,

which they hold tight in front of their faces, with just a crack for the

eyes. This is so that the men may not see their beauty as they go

through the city.

|

|

Leaving the markets, we walk through the crowd up the

street till we come to the little temple containing the bell which sounds

the opening and closing of the gates.

This is in the business center of the city, and the streets

surrounding it are thronged with merchants and peddlers, with dandies and

loafers, from sunrise to sunset. The ordinary Korean store is a little

booth or straw shed which juts out into the street, and which contains,

perhaps, a bushel-basketful of goods. The merchants wear white gowns

and black hats, and we see them squatting outside their stores with their

hats on, smoking as they wait for their customers.

About the little temple there are large buildings or bazaars,

each of which is devoted to the selling of one kind of goods. These buildings

have many little rooms, each the size of very small closet, and every little

room is a store. The merchants sit in the halls outside the closets,

with their hats on, and bring out piece by piece as you order. They

are by no means anxious to sell, and the more goods you want, the higher

the price they will ask.

|

|

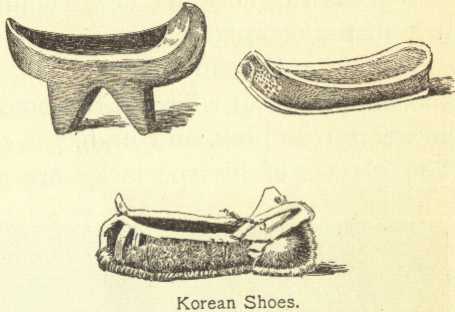

You may get one pair of shoes, for instance,

for fifty cents, but if you want a hundred, the merchant will be very sure

to charge you at least a dollar a pair, on the plea that if he sold all

his goods he could not keep his store open.

|

|

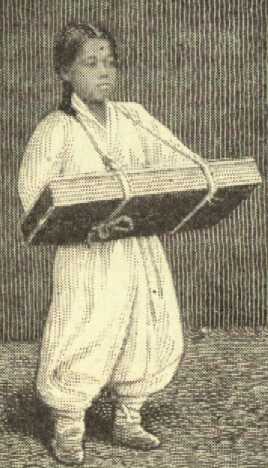

A great deal of peddling is done by boys, some

of whom have fires on the streets, on which they roast chestnuts to sell

hot from the coals. We meet little fellows everywhere peddling candy.

They have trays which hang from their shoulders at right angles with their

waists, and their money boxes consist of pieces of twine, upon which they

string the Korean “cash” which serve as the money of the country.

These cash are about the size of an old-fashioned red cent, with a square

hold cut out of the center. It takes more than two thousand cash

to equal the value of one of our dollars, and we find that in taking a

long journey we must have an extra bullock, or a couple of porters to carry

the money we need to use on the way.

|

"Peddling candy"

"Peddling candy"

|

|

What is the noise we hear coming from that little

hut just off the main street?

That is a Korean school. The teacher squats on the

floor in a gown of white or of some bright color. Today he wears

rose pink, and he has a cap of black horsehair. The glasses of his spectacles

are as big as trade dollars, and his appearance is very imposing.

His scholars squat about on straw mats studying their lessons out loud.

They sway themselves back and forth as they sing out again and again the

words they are trying to learn, all shouting at once. If one stops,

the teacher thinks he is not studying, and calls him up for a whipping.

At our request, the teacher shows us how scholars are punished. A

little fellow, well knowing that he has done nothing wrong and will not

be hurt, stretches himself on his stomach flat on the floor, while the

teacher takes a rod and taps him a few blows on he thighs. We laugh.

The little Korean laughs too, and when we have given him some coins worth

about a cent of our money, he runs back to his seat, the happiest, as well

as the richest, boy in school.

The studies of Korean boys are made up chiefly of learning

by heart the sayings of great Chinese scholars. They do not now have the

advantages of our American children, but changes are going on in the country,

and the little Koreans will soon have schools like our own.

It is through public examinations that the officials of

the country are chosen. The Koreans have great respect for good scholars.

They are lovers of poetry. Young men often have poetry parties, where

each guest shows his skill in writing verses upon a subject given out at

the time.

|

|

We find other curious customs, some good and

some bad, which have grown up during the ages the Koreans have lived by

themselves. The people have much natural refinement. They are

intelligent and kind, and, as we travel among them, we feel that with a

good government, new laws and equal rights for all men, they will make

as respectable a little nation as can be found anywhere. They are

improving their country. There are electric lights and electric cars

in Seoul, and new railroads are fast being built.

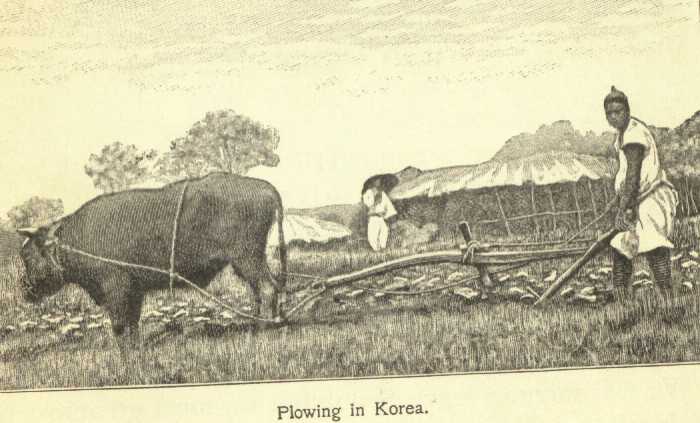

We feel sorry to leave Seoul, but we must go across the

peninsula to the east coast, in order to get a ship for Siberia.

We travel on ponies, riding for seven days up and down the mountains, passing

through thousands of rice fields, and now and then skirting the wilds where

we dare not do after dark for fear of the tigers. We find numerous

villages of thatched huts, and notice that the farmers live in villages

and not on their farms. We stop sometimes at Korean inns, where we

sleep on the brick floors, half baked by the straw fires beneath us.

Sometimes we stay with the magistrates, who, on our departure, as a mark

of honor furnish us with trumpeters to toot us out of the town. At

last we reach the fine harbor known as Gensan. Here we board a Japanese

steamer on its way from Nagasaki to Vladivostok, and after a few days’

sail northward we find ourselves at anchor in the Gulf of St. Peter the

Great, with the largest seaport of Siberia lying before us.

|

|

|