A short sail from Japan brings us to the land

of big hats and long gowns, the land of the Korean, the curious people

who have gained the title of "The Hermit Nation" . We knew nothing

about them until a short time ago, yet they existed as a nation two thousand

years before America was discovered, and their history records their doings

as far back as twelve hundred years before Christ. This kingdom is

now largely controlled by Japan.

|

|

The Koreans have always looked upon their

country as the most beautiful of the world, and have tried to keep other

nations from learning about it, for fear that they might come and seize

it. For this reason the Koreans have until lately driven travelers

away from their shores, and when sailors were shipwrecked there, they were

not permitted to leave, lest they might carry the news of Korea to their

homes.

You have learned how the United States introduced

our civilization into Japan. It also opened Korea to the rest of

the world. In 1882 one of our navel officers, Commodore R.W. Shufeldt,

was sent to this country. His vessel entered the harbor of Chemul-pho,

and he there made a treaty by which the King of Korea consented to open

his land to all nations. Since then travelers have been permitted

to go where they please. The Koreans are now exceedingly hospitable.

We shall find ourselves treated as guests, and we can learn much about

this curious country.

Korea is a mountainous peninsula of about the same

shape as Florida, and not much greater than Kansas in area. It is

bounded on the northwest and northeast by Manchuria and southeastern Siberia,

and is separated on each side from Japan and China by boisterous seas.

Its shores are rocky and peppered with islands. It contains many

fertile valleys covered with rice, and streams by the hundred flow down

its green hills. We shall find its soil rich, but nowhere well farmed.

The climate is much the same as that of our North Central States, and we

shall notice that the trees are not very different from those we have at

home. In the mountains there are rich mines of gold, and valuable

coal fields which have not yet been worked; and in a recent trip across

the country the author saw many signs of petroleum.

Korea has numerous birds and many wild animals.

We shall not dare to travel at night for fear of the tigers, and we may

shoot a leopard as we ride through the mountains. The country contains

about twelve million people, who live in a few large cities and numerous

villages. Both the towns and their inhabitants are unlike those of

any other part of the world, and we rub our eyes again and again, wondering

whether we are really still on our own planet, or whether by magic during

the night we have not sailed into one of he stars, or perhaps into the

lands of the moon.

We sail around the foot of the peninsula and

halfway up the west coast until we come to the harbor Chemulpho.

This is the port for the capital, the city of Seoul, which is situated

twenty-six miles back from the seacoast, on the other side of a small mountain

range, We see white-gowned figures walking like ghosts over the hills

as we enter the harbor, and a crowd of Koreans surrounds us as we land on

the shore.

What curious people they are! Many of them

dress like women, but their faces are men's. They are not Chinese,

and still they are yellow. They are not Japanese, thought their eyes

are like almonds in shape. They are taller than the Chinese we have

in America, and their faces are kinder, though a little more stolid.

They have cheek bones as high as those of an Indian, and their noses are

almost as flat a negro’s. They are stronger and heavier than the

men of Japan, and some carry great burdens of all kinds of wares.

|

|

Here comes one trotting along with a cart load

of pottery tied to his back. During our journey through the mountainous

parts of the interior, men of that kind will carry our baggage, weighing

hundreds of pounds, twenty-five miles for a very few cents. They

will fasten our trunks to an easel-like framework of forked sticks which

hangs from their shoulders, and they are so strong that they will trot

over the hills as though they were loaded with feathers. Such men

are Korean porters. They still carry much of the freight of the country,

and they form but one class of this curious people.

|

|

At the top there is the king, who governs the

country, and who has vast estates and acres of palaces. He lives

in great state, and his officials must all get down on their knees when

they meet him. There are nobles by hundreds, who strut about in gorgeous

silk dresses, who own the most of the land, and who live by taxing the

rest of the people. They are the drones of the country. They

spend their days in smoking and chatting, and they fan themselves as they

ride through the streets in chairs carried by their big-hatted servants.

There are government clerks by the thousand, dressed

in white gowns, who earn their living as scribes for the nobles.

They act as policemen and tax-gatherers, and often oppress the people below

them. There are farmers, merchants, mechanics, and slaves; and the

men of each class have their own costume, by which we may know them.

The gowns of the clerks have tight sleeves, while those of the nobles are

so big that they hang down form their wrists like bags. No one can

do hard work with this arms enveloped in bags, and the sleeve of a Korean

noble cold hold a baby.

We see servants and slaves dressed in jackets and full

pantaloons of white cotton. They have stockings so padded that their

feet seem to be swelled out or gouty, and almost burst the low shoes which

they wear. The gowns are of all colors, from the brightest rose pink

to the most delicate sky blue, and the men who wear them go about with

a strut, and swing their arms to and fro, as they walk up and look at us,

the strange foreigners who have come to their country.

But the queerest of all, to our eyes, are the hats

and headdresses. Some heads show out under great bowls of white straw

as big as an umbrella, and others are decorated with little hats of black

horsehair, which cover only the crown of the head, and which are tied on

the ribbons under the chin. This is the high hat of Korea, which,

like our tall silk hat, is considered the mark of the gentleman; and as

we go on we shall find that each hat has its meaning.

|

|

Here comes one bright straw, as large round as

a parasol, which seems to be walking off with the man whose shoulders show

out beneath it. That man is a mourner for, according to the Korean

belief, the gods are angry with him and have caused the death of this father.

For three years after the death of a parent the

Korean wears a hat of that kind. He dresses in a long gown of light

gray, and holds up a screen in front of this face to show his great grief.

During this time he dare not go to parties, and he should not do business,

or marry. If, at the end of this mourning, the other parent should

die, he must mourn three years longer; and when the king or queen passes

away, all the people put on mourning for a season.

|

|

But there come two men with no hats at all. They

look very humble, and they slink along through the crowd, as if ashamed.

They part their hair in the middle, and wear it in long braids down their

backs. Those are Korean bachelors, and until they are married they

will have not rights which any one is bound to respect. Only married

men can wear hats in Korea, and those without wives, weather they be fifteen

or fifty, are boys and are treated as such.

Married men wear their hair done up in a topknot

of about the size of a baby’s fist. This is tied with a cord, and

it stands strait up on the crown of the head like a handle. Unmarried

men and boys are obliged to wear their hair down their backs. They

tie the long braids with ribbons, and look more like girls than boys.

The Korean women, as we shall learn farther on, are seldom seen on the

streets, and we meet only men and boys at the landing.

But let us travel over the mountains, and visit the great

city of Seoul. It is the largest city of Korea, and it is the home

of the king and his court. It is only twenty-six miles from Chemulpho,

the chief seaport, and there is a railroad connecting the two places.

We shall travel in the old Korean fashion, however. We ride in Korean

chairs, each of the party sitting cross-legged in a cloth-lined box swung

between poles and carried by four big-hatted coolies. As we go, we

tremble at the prospect of not reaching Seoul before dark, for we fear

that we might have to stay outside all night if we should get there after

sunset.

The Korean capital is surrounded by a massive stone wall

as tall as a three-story house, and so broad at the top that two carriages

abreast could easily be driven upon it. This wall was built by an

army of two hundred thousand workmen five hundred years ago for the defense

of the city, but it is in good condition today, and it can be entered only

by the eight great gates which go through it. These gates are closed

every night just at dusk by heavy doors plated with iron, which are not

opened again until about three o’clock in the morning. The signal

for their closing, as for their opening, is the ringing of a big bell in

the center of the city, after which those who are outside cannot get in,

and those who are inside cannot get out. We now but one word in Korean,

which means "go on," or "hurry". We cry out this word again and again,

until we are hoarse. Our coolies go on the trot, and we reach Seoul

in time to climb to the top of the walls and take a view of the city before

the gates close.

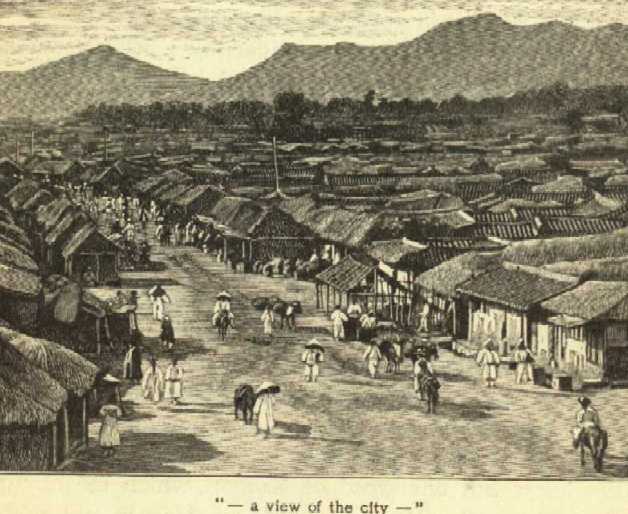

Seoul lies in a basin surrounded by mountains,

which in some places are as rugged and ragged as the wildest peaks of the

Rockies, and which in others are as beautifully green as the Alleghenies

or the Catskills. The tops of these mountains rest in the clouds,

and as we look we see watch fires burning upon them, and learn that these

form the telegraph system of Korea. They are the last of a series

of fires which flash from hill to hill all over the country and by their

number and size tell the king whether the people of his various provinces

are at peace or about to break out into war. The wall around the

city climbs upon these mountains. It bridges a stream at the back.

It runs up and down hill and valley, enclosing a plain about three miles

square, in which lies the city of Seoul.

|

|

What a curious city it is! Imagine three hundred

thousand people living in one-story houses. Picture sixty thousand

houses, ninety-nine out of every hundred of them build of mud and thatched

with straw. Think of a city where the men are dressed in long gowns,

where the ladies are not seen on the streets, and where the chief businesses

of all seems to be to smoke, to squat, and to eat; and you have some idea

of Seoul.

It is altogether different from our cities of the

same size. Cut the houses of a great American city down to the height

of ten feet, and how would it look? Tear away the walls of brick,

stone, and wood, and in their places build up structures of cobblestones

put together with un-burnt mud. Slice the big buildings into little

ones, and move the mud walls out to the roadway. Next, run dirty

ditches along the edges of the now narrowed streets. Cover the houses

with straw roofs, and over the whole tie a network of clotheslines; and

you have a general idea of the Korean capital.

As you look, you think of a vast harvest field filled

with big haycocks, interspersed here and there with tiled barns, and with

a great enclosure of more imposing barns under the mountains at the back.

The haycocks are the huts of the poor, the tiled barns are homes of the

nobles, and the great enclosure contains the palaces of the king.

The nobles live in large yards back from the street. Their houses

look much like those of Japan. They have walls of paper between the

rooms, and they are heated by flues which run under the floor.

|

|

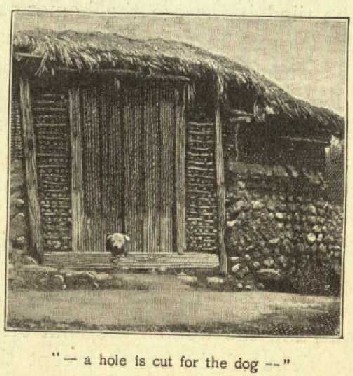

The huts of the poor which make up the greater

part of the city, are built each in the shape of a horseshoe, with one

heel of the shoe resting on the street, and the other running back into

the yard. In the houses of both the rich and the poor the men live

in the front, and the women are shut off in the rear. They have no

views of the street except through little pieces of glass about as big

as a nickel, which they paste over holes in the paper windows. The

doors which lead into these houses are of the rudest description.

They are so low that you cannot go in without stooping. At the foot

of each door a hole is cut for the dog, and every Korean house has its

own dog, which barks and snaps at foreigners as they go through the streets.

|

|

But, as we are looking over Seoul, the sun drops down

back of the mountains. The great bell in the center of the city peals

out its knell, and the keepers close the gate doors with a bang.

Similar ceremonies are going on at the other gates of the city, and that

bell, like curfew of the Middle Ages, sounds the close of the day.

We climb down the steps on the inside of the wall, and take our seats again

into our chairs. We do not go to a hotel, but our coolies take us

to the home of the American minister, who is a friend of the author, and

who entertains us during our stay.

|

|

NEXT: Travels Among the Koreans

|